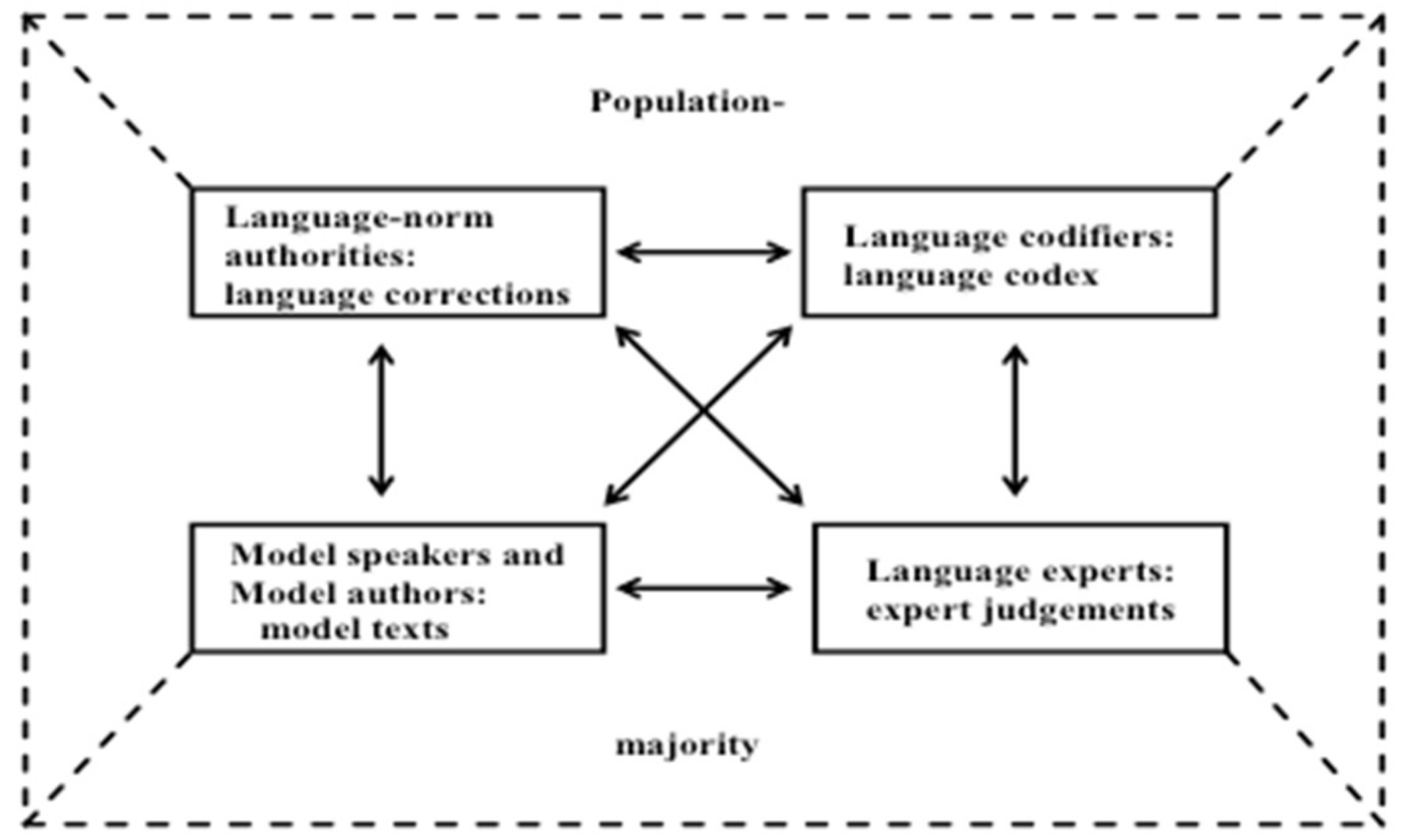

Das soziale Kräftefeld der Standardsprache

Social forces that determine what is

standard in a language

Language-norm authorities and their prescriptions

Any individual who has the power, however established, to effectively correct

other individuals' speech or writing is a language-norm authority, like for

example any grandmother vis-à-vis her grandchildren or any older vis-à-vis her

younger siblings. For standard varieties there are, however, professional language-norm authorities with

language correction as part of their professional tasks, like school teachers,

radio and TV directors, copy editors and also superiors in offices, especially of

the state administration, but also in private companies. They are typically not

only entitled to correct their language-norm subjects' language behaviour, but

even obliged to do so.

Model speakers, model authors and model texts

The public sphere is naturally one of the primary arenas where the norms of standard varieties become established. The social forces

which play a major role in this arena are what I call the model speakers and authors.

Their main members are, as a rule, professional

speakers and authors in the mass media: newsreaders and journalists for

major, especially national, radio and TV channels or newspapers and journals.

They produce the model texts. They confirm the existing standard variety

norms on the one hand, but are the sources of new norms or of norm changes

on the other hand. Once language forms have come to be used regularly in

these arenas, they are standard.

Language codifiers and language codex

Codification is another crucial difference between standard varieties and non-standard

varieties. A language codex, which contains the results of codification and is

usually published, is fundamentally different from a mere linguistic description,

which can also exist for non-standard varieties. For language codices, it is

definitional that they serve as guides for correct language use or for language

correction. Such prescriptive function may very well counteract the intentions

of the authors who have compiled the codex and who mostly typically claim

that they just wanted to provide a description. However, actual functions, not

authors' intentions, are decisive for a dictionary, a grammar or the like to be a

language codex

Language experts and expert judgments

Whenever a new edition of the language codex or a part of it appears, it will be

reviewed by language ex perts, i.e. linguists. I call this separate group

"language experts (with respect to codification)". They are different from the

codifiers, but both groups overlap if codifiers review parts of the codex written

by others. The language experts are, generally speaking, all those whose

reviews of the language codex are, or have a chance of being, taken seriously.

They have a potential im pact on what is or what is not standard in the

respective language if their criticism of the codex flows into its next edition.

Interactions between roles

The model speakers and authors have been trained by language- norm authorities on the basis of the

language codex, which th ey sometimes check for their texts. The model

speakers and authors are, in turn, pe rceived by the other three forces and

carefully observed by the codifiers who, as a rule, use their texts as the most

important source for codex revisions or supplements. This is necessary,

because the model speakers and authors tend to change the language forms

they use in the course of time, in spite of keeping in touch, though mostly

indirectly, with the codex. Changes are most frequent and more salient in

vocabulary, but also occur in grammar, pragmatics and pronunciation over the

years. The model authors and speakers lead the pack of the four social forces

as to innovations, with the codifiers following suit – though they may, as we will

see, be the transmitters rather than the immediate creators of innovations.

Even the language-norm authorities use the model speakers' and authors'

texts, mostly inadvertently, as a guideline for their language correction. In

addition, the language experts rely on them in their criticism of the codex.

source