Elements of power-sharing, consociational or consensus democracy, which the Swiss call ‘system of concordance’. has two main characteristics:

- The executive is composed of a grand coalition. The goal is to let all important political forces participate in governmental politics, and to share the political responsibility with all these forces.

- Political behaviour within this grand coalition is geared towards permanent negotiation and compromise.

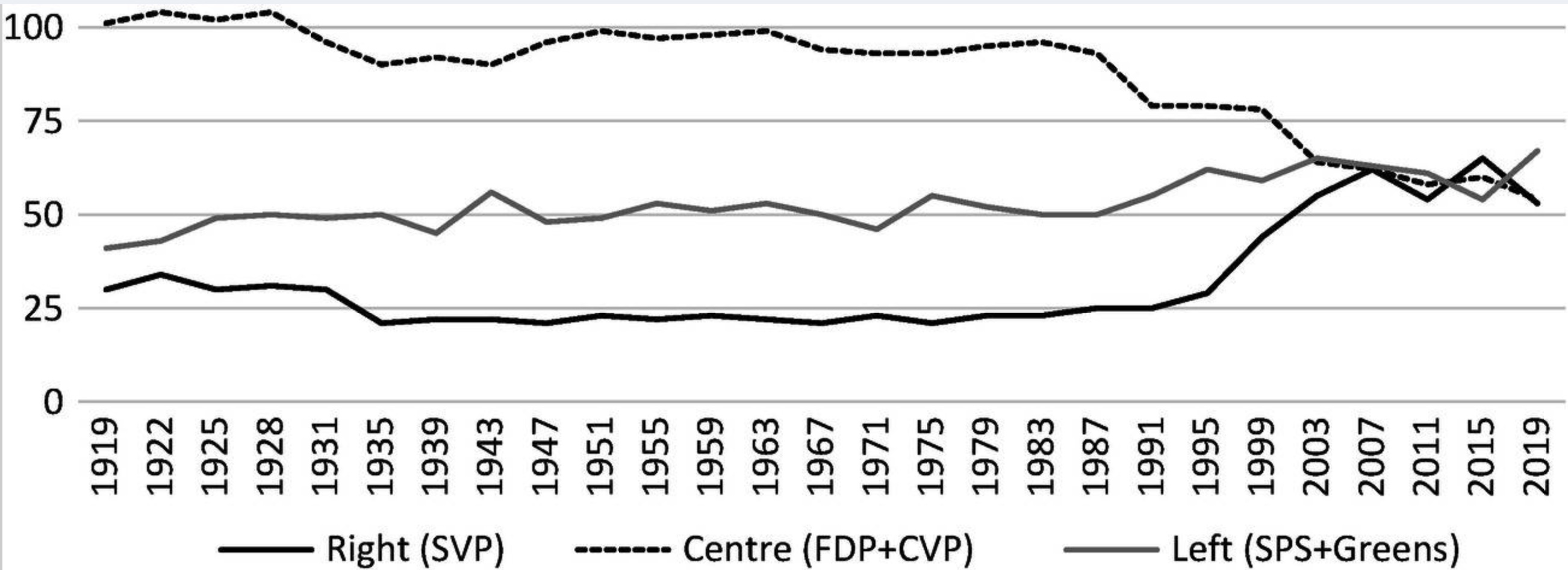

Distribution of positions in the Federal Council by party:

Distribution of seats in the National Assembly by political camp:

Parliament (Nationalrat & Ständerat):

According to the ideas of the fathers of the Constitution of 1848, the two chambers of parliament were the ‘highest authority’ of the federation. Indeed, until today parliament has a lot of power. Besides its main function of law-making, it elects the members of the Federal Council and the Federal Supreme Court, supervises the administration and can intervene in many ways. As there is no vote of confidence to bring down the government, parliament is free to criticise the projects of the Federal Council or even to reject them.

Direkte Demokratie / Direct democracy:

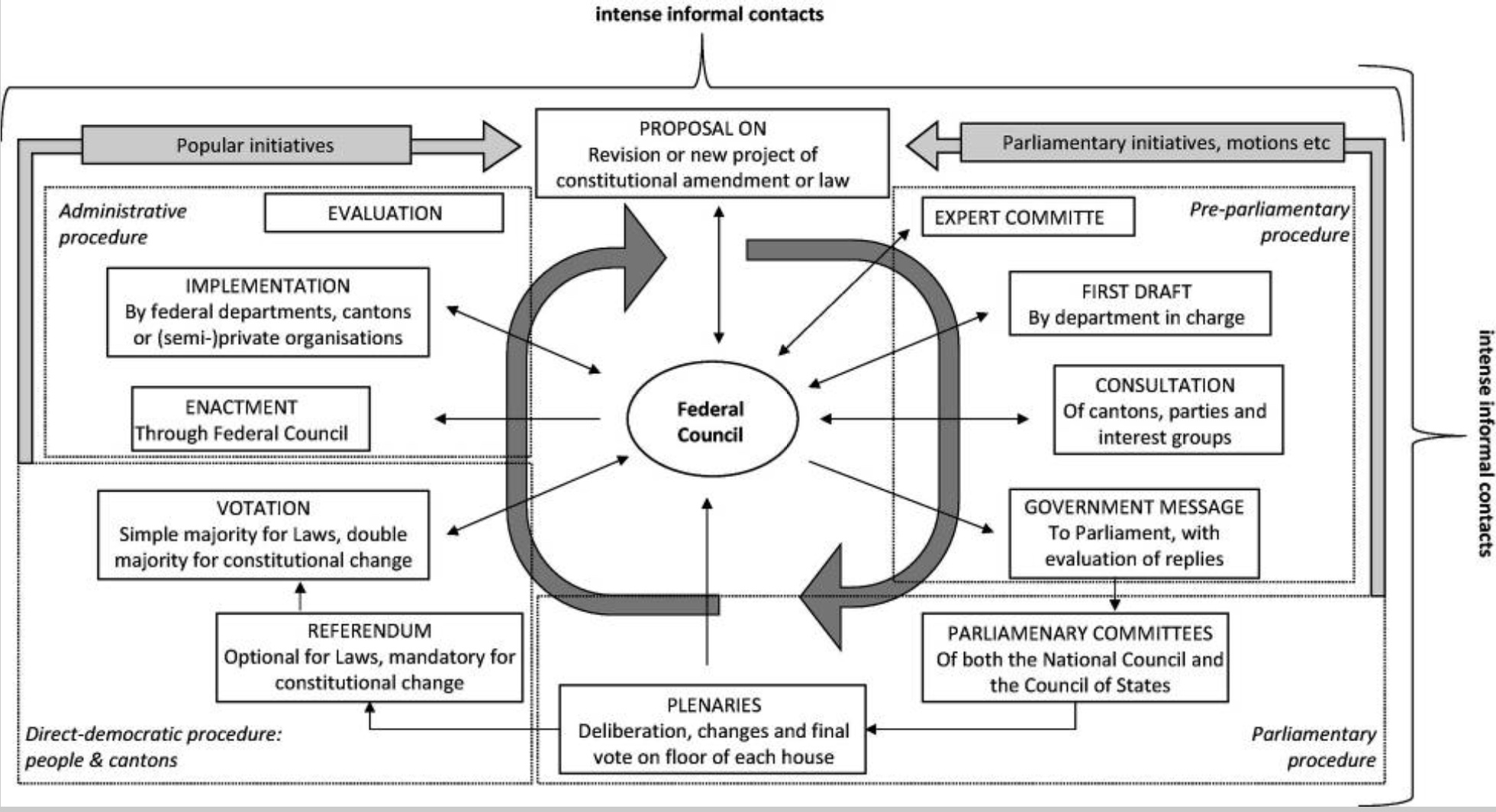

Direct democracy began to play an important role when the people’s rights, originally restricted to the constitutional referendum, were extended to the optional referendum (1874) and then the popular initiative (1891).

Interessensgruppen / Interest groups:

Their prime arena of influence is the pre-parliamentary procedure, which was institutionally formalised after World War II. Note that participation in expert committees and the pre-parliamentary consultation is open not only to economic associations such as employer’s and trade unions, but also to other organisations, the cantons and even private individuals. We have already shown why in Switzerland interest groups have more influence in the pre-parliamentary phase than elsewhere: their additional bargaining power lies in the fact that they can use the referendum threat as a pawn.

Die Kantone / Cantons:

In Switzerland, the 26 cantons are not only largely autonomous, more or less self-contained polities. They also, and increasingly, try to influence the federal government to act or refrain from acting in a certain way.

Der Bundesrat / The Federal Council:

The main function of the Federal Council is the steering of the entire political process. Giving the go-ahead for most formal steps of decision-making, setting priorities in substance and time, the Federal Council has a great influence on the political agenda. It disposes of all the professional resources of the administration, which allow it to prepare its own policy projects. Political leadership of the Federal Council is limited, however, for two main reasons: consensus in an all-party government is difficult to achieve and often minimal in scope, while parliament, not obliged to support the government because there is no vote of confidence, can always turn down the propositions of the Federal Council. In foreign policy, however, the leadership of the Federal Council is more pronounced.

The entire political process aims at reaching a political compromise. Instead of a (small) majority that imposes its solution onto a (large) minority, we find mutual adjustment: no single winner takes all, everybody wins something.

Some people attribute this behaviour to a specifically ‘Swiss’ culture. From a political science perspective, however, the effect of institutions seems to be paramount. The referendum challenge, the strong influence of cantons and interest groups as well as the multiparty system amount to formidable veto points that simply do not allow for majority decisions and compel political actors to cooperation and compromise. This means that every actor must renounce on some of their expectations, which is not always easy.

Consensus, theoretically, requires a Pareto optimal solution in which no actor is left with losses.

Game theory shows that in a single game, self-interested actors defect from cooperation when it offers them an extra profit. This risk is considerably reduced if the same actors play many games. In this case, players may mutually sanction defection, which then becomes less attractive. This is exactly the case in a steady power-sharing arrangement, as it allows actors to develop mutual trust.

Power-sharing produces strong formal and informal contacts amongst the entire political elite. The theory of ‘consociationalism’ proposes that power-sharing also leads to the development of common values and attitudes.3 Elites develop a common way of understanding problems which must be solved, and they learn to adopt perspectives that go beyond their specific group interests.

Linder, Wolf, and Sean Mueller. “Consensus Democracy: The Swiss System of Power-Sharing.” In Swiss Democracy, by Wolf Linder and Sean Mueller, 167–207. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63266-3_5.